U.S. Public Pension Assets Hit Record High

Asset values at U.S. public pension funds rose 8.4 percent in the latest fiscal year to the highest level in more than 40 years, but their costs also rose, the U.S. Census reported on Monday.You can read a summary of the Quarterly Survey of Public Pensions here. The report is encouraging and provides more evidence that rising returns are bolstering U.S. public pensions. And if assets keep rising along with interest rates, the funded status of these state plans will improve further.

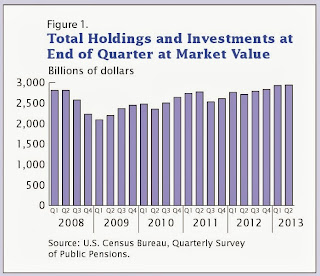

Most retirement systems ended fiscal 2013 on June 30. In the final quarter of that fiscal year the cash and securities holdings of the 100 largest public-employee pensions were $2.944 trillion, up 8.4 percent from a year earlier and the highest level since the Census began collecting pension data in 1968.

Still, quarterly growth in their investments has been slowing at the same time they are having to pay more to retirees. Benefits and withdrawals also reached record highs in the quarter, jumping 16.8 percent from a year earlier to $62.2 billion.

"It looks like we're stabilizing instead of growing," said Erika Becker-Medina, chief of statistics in the Census governments division. She noted that on a quarter-to-quarter basis, the assets level was up just 0.4 percent.

Investments provide the lion's share of retirement system revenues, with employers and employees also pitching in funds. During the 2007-09 recession, the financial crisis caused those investments to crumble just as states confronting collapsing revenues cut their pension contributions and also laid off employees.

Pensions have slowly marched back to health since holdings reached a low of $2.1 trillion in 2009. In fiscal 2013, investments finally surpassed the peak they reached in 2007 before the recession began.

Governments across the country have reformed pension policies in the aftermath of the funding crisis. Some began making the full contributions that their actuaries suggest. Others have had employees pitch in more, raised retirement ages, and cut annual cost of living adjustments to benefits.

The Census data showed that governments and employees both are now pitching in greater amounts of money.

Government contributions increased over the year by 2.3 percent to $22.8 billion, while employee contributions rose 11.2 percent to $11.4 billion. Government contributions have been creeping up over the last few years, Becker-Medina noted, pointing out that in the quarter that ended on June 30, 2008, government contributions were $18.39 billion.

"This data confirms what we've been seeing, which is that strong equity markets and increasing contributions from both employers and employees are driving higher public pension asset values," said Keith Brainard, research director at the National Association of State Retirement Administrators. "While quarterly and annual changes in contributions tend to be steady, investment earnings typically are lumpy and more volatile."

Over the year, corporate stock holdings of pension plans increased 7.4 percent to $1.01 trillion and their international securities rose 16.8 percent to $592.6 billion. U.S. government securities rose over the year by 6.9 percent to $267.1 billion. Corporate bond holdings fell 9 percent to $330.8 billion.

Retirement systems' earnings on investments were $38.28 billion in the quarter, down from earnings of $115.49 billion the previous quarter but better than $16.3 billion in losses they had in the same period in 2012.

Public pensions "have stood out in returns versus other institutional peers for the primary reason that one of the assets classes that held up well in the second quarter was U.S. equities," said Steve Foresti, managing director and head of the Investment Research Group at Wilshire Consulting in Los Angeles.

Wilshire recently found that for the year ended June 30, public pensions had a median investment return of 12.4 percent. Most pensions plan for returns of between 7 and 8 percent.

During the quarter, the Dow Jones industrial average rose 2.3 percent, the Standard & Poor's 500 2.4 percent, and the Nasdaq 4.2 percent.

The S&P 500 had the strongest first half of any year since 1998, as well. The final two quarters of most pensions' fiscal years represent the first half of calendar 2013.

The retirement systems' financial reports for fiscal 2013 will not be released for a while. Looking at the financial reports for fiscal 2012, Wilshire found that the median funding level for 134 state pensions was 71 percent, meaning they have enough assets to cover 71 percent of their costs.

"With their asset allocation and how markets have performed, I expect to see improvement," said Foresti about the funding level for fiscal 2013. "I'd estimate they will be 75 percent."

Nevertheless, even as assets hit a record high, there are reasons to be concerned. First, costs are rising and both employees and employers are paying more into these state plans. Second, benefits and withdrawals also reached record highs in the quarter, jumping 16.8 percent from a year earlier to $62.2 billion. Third, even though the funded status has improved in the last few years, many state plans are still in terrible shape and reforms are needed to bolster them and ensure their long-term sustainability. The new GASB rules, which will slash projected rates of return for public pension funds' unfunded portions from roughly 7.5 percent to a much lower market level, will hit many public pensions hard.

One of the reforms I keep harping on is improving the compensation for U.S. pension fund managers. In his parting interview to the FT, Larry Schloss, the understated private equity expert who safeguards the pension money for New York City’s police officers, firefighters and teachers, discussed some of the problems he encountered during his tenure:

New York’s pension system seems archaic compared with more advanced peers in the field. First, there are five distinct funds: one for teachers ($50bn); another for firefighters ($9bn); a third for police officers ($30bn); a fourth for city workers ($48bn); and, lastly, one for people who work at schools but are not educators ($3bn).Mr. Schloss raises excellent points that need to be addressed by many U.S. public pension plans. In particular, an inadequate compensation scheme is a huge obstacle for leaders trying to attract and retain talent to their public pension fund to lower costs by managing assets internally.

Each union employs its own trustees, even though the groups share about 90 per cent of investments. Much to Mr Schloss’s chagrin, a proposal to merge the five investment committees into a single one to cut costs failed, thanks to political undercurrents.

Another pitfall is that, unlike peers such as Calpers and Calstrs, California’s two big pension funds, the city’s pension group outsources all its investments to BlackRock and 324 other financial managers. It thus invests only in funds. “Consequently, we pay fees to everyone ... It’s a bit odd that New York City, the world’s financial capital, outsources all of its investment management to money managers,” laments Mr Schloss. “You’ll save money on the margin if you do it in-house. The key is not to give up the returns.”

He adds: “We have $140bn in assets and we don’t own one property because it’s all in funds ... I think we should own some buildings and save on fees and do joint ventures with people.”

Bringing people on board to manage money is also a tedious process, due in part to rules brought in years ago after a corruption scandal. While the time it takes to hire a manager has been shortened to nine months from about 17, the rules are the same ones the city uses to “buy school buses and pencils,” notes Mr Schloss.

Mr Schloss laments that he does not pay his staff well. The average person who works in New York’s bureau of investment management makes $100,000 and must live in one of the five boroughs. “It’s not enough,” says Mr Schloss. “If you come out of Harvard Business School and get a starting job at a bank, you get a couple of hundred thousand dollars.”

Mr Schloss’s departure from the job seems bittersweet as he got such a kick out of it. He is not lobbying for a second act at the municipal building, but he makes the case that the unspoken rule that the new comptroller brings his own chief investment officer works against investors’ interests. “It’s not the right way to manage money,” he concludes. “If you look at some of the other public pension funds, you’ll see that the chief investment officer is more of a staff job, and the group in the investment office stays, no matter who the elected officials are.”

Importantly, this is the primary reason U.S. public pension funds are trailing their Canadian peers and unfortunately, there is no political will to change compensation and set up independent investment boards that operate at arms-length from the government.

Finally, while the state of U.S. public pension plans is improving, hedge funds and private equity funds are thriving...no thanks to them:

The reason for the continued success of hedge funds and private equity funds is actually quite simple – investors love them!The symbiotic relationship between U.S. public pension funds and the alternatives industry is an interesting topic which is a lot more complicated than this article leads you to believe. It's not just about chasing yield, there are governance issues and political reasons that explain why assets of the top alternative asset managers have soared to record levels after the crisis. But there is no doubt U.S. public pension funds are fueling this growth, paying high fees and not always getting the returns they expect.

Of course, there were doubts and recriminations that surfaced again and again at the end of 2008 and the beginning of 2009. Of course, there were investors that suffered eye-watering losses on their fund investments who would require some coaxing (and a little TLC) before their would allocate money again.

But when fund after fund continued to post high investment returns, and the rest of the financial markets seemed to oscillate between pessimism and indifference, investors began writing checks again. With replenished war chests, hedge funds and private equity funds were back in business.

So long as these funds can credibly promise high returns, there will be a steady flow of investors willing to back them. Once accumulated, the money is deployed wherever the men and women running them feel there is an opportunity to profit. This industry is driven, first and foremost, by the confidence level of these investors.

Despite the vitriol that is on occasion directed and the mangers that profit from their funds successes, surprisingly little attention is given to those institutions that are their lifeblood.

Critics expecting to see money flowing from the trust funds and the personal estates of the 1% are often surprised to learn that most of the money in private equity funds and most of the new money going into hedge funds actually comes from US public pension plans, both big and small, that provide retirement benefits to teachers, firemen, police and other government workers across the country, as well as the generous endowments of many leading colleges and universities. Not wealthy plutocrats dressed like the man from the Monopoly board game, with a cane and top hat the accessorize his formal morning suit.

So long as these pension plans offer their beneficiaries gold-plated retirement benefits, money will need to earn high rates of return in order to fund these payments. And despite the ample criticism that has been lobbed at hedge funds and private equity funds since 2008, there has been little traction in attacks on the premise that the best funds really don't deliver high returns. Certainly not all funds are able to deliver the jaw-dropping returns, but enough are to maintain the momentum of investor allocations necessary to keep the industry afloat.

If there is to be a day of reckoning for hedge funds and private equity funds, it will necessarily only spring from a crisis in confidence in the minds of those individuals in California, New York, Texas and many other states who have as their main priority ensuring that retirement checks get sent to former public workers when there are due.

Until then, checks will continue to be written by investors eager to earn 20-30% on their money, and managers of alternative funds will still eagerly cash those checks and then promptly look for opportunities in the market that they can pounce on to quickly double and triple their money.

Below, Lawrence Schloss, New York City's chief investment officer and deputy comptroller for pensions, talks about the city's pension fund returns and investment strategy. He speaks with Scarlet Fu on Bloomberg Television's "Money Moves," and raises the issue of how low compensation is plaguing U.S. public pension funds.