Outlook 2016: The Deflation Tsunami Cometh?

Morris Bechloss wrote a comment for The Desert Sun, When Will Deflationary Blight End?:

Importantly, I don't see any end to the deflation supercycle and have outlined six structural themes which support my long-term outlook on global deflation:

And all this financial risk-taking can end very badly in a deflationary environment. In fact, Graham Summers, Chief Market Strategist for Phoenix Capital Research published a comment, Deflation is Back… Will It Lead to Another Market Crash?:

It's not that I disagree with his main thesis -- namely, the world has a major deflation problem which is causing policymakers all sorts of angst and can lead to a huge market crash -- but when I read stuff like "central banks are running out of ammo," I just tune off.

Why? Because as I've repeatedly explained, despite Ray Dalio being worried about the next downturn, central banks have plenty of options beyond zero rates and more QE as they try to save the world from a prolonged period of debt deflation and one of those options is negative interest rates which have been used in Switzerland and elsewhere in Europe and are coming to Canada in the near future.

All this to say, despite what Ray Dalio and Bill Gross think, the Martingale casinos aren't about to go bust any time soon and central banks are a lot more clever than hedge fund and market gurus give them credit for.

Having said this, central banks are not going to solve all the world's economic and financial ills and there are serious challenges ahead which will only get worse once global deflation sets in.

On this last point, Carmen Reinhart, Professor of the International Financial System at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government wrote a great comment for Project Syndicate, A Year of Sovereign Defaults?:

In fact, The Economist notes Brazil’s economy may be 8% smaller than it was in the first quarter of 2014, when it last saw growth; GDP per person could be down by a fifth since its peak in 2010, which is not as bad as the situation in Greece, but not far off. Moreover, Brazil's debt is expected to reach 93% of GDP in 2019, a situation which can quickly become untenable if the global economy sinks into deflation.

Also, Bloomberg reports South Korea’s biggest brokerage predicts the won is headed for its steepest annual slide in eight years as the government favors depreciation to revive exports and stave off deflation.

South Korea's economic woes will only get worse if China's slowdown persists as it grapples with deflation. JP Smith, who worked at Deutsche Bank before leaving last year to start independent research firm Ecstrat, says conditions in China look as ominous as those in the U.S. on the eve of the 2008 financial crisis, and in Korea just before the 1997 Asian crisis. As a result, Chinese stocks face greater downside potential than those of any other global market, he wrote in a Dec. 17 report.

And if China decides to once again devalue its currency, it will have ripple effects throughout Asia, including Japan where the prime minister and central bank governor have applied fresh pressure on companies to do their part in putting a sustained end to deflation by boosting wages and investment, with little success.

All this to say keep monitoring emerging market currencies in 2016. This is where you will see the global battle against deflation take place. Unfortunately, it's a losing battle and one that will export disinflation and deflation throughout the world at the worst possible time.

In my opinion, the problems in emerging markets are only going to get worse in 2016 so I have a hard time buying the global recovery theme which some elite funds are betting on. Even Canada's large and powerful pensions are betting on energy but those investments might not pan out for years or worse still, decades if global deflation sets in.

Above, I've given you my broad global macro thoughts for the year. I see deflationary headwinds picking up all over the world, especially emerging markets where the risks of another financial crisis are rising. I see no global recovery taking place and think those betting on one are going to once again be sorely disappointed.

Interestingly, in his 2016 Economic Outlook: Consensus and Other Views, Ted Carmichael does a masterful job demonstrating just how (overly) optimistic consensus forecasts are for 2016. I highly recommend you to read his entire comment here where he's very careful and much more balanced than most economists out there and concludes by noting the following:

Bearing the above global macro outlook in mind, I will now shift my attention to markets.

First, Julie Verhage of Bloomberg did a great job going over the best and worst-performing assets of 2015, a year where nothing worked for global asset allocators. You should take the time to look at the charts she posted in her comment.

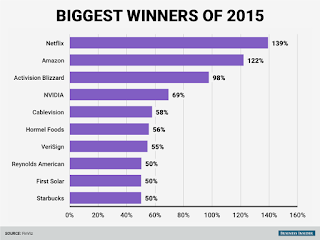

What else? Sam Ro and Andy Kiersz of Business Insider went over the S&P 500's 10 biggest winners and 10 biggest losers of 2015:

If you believe in the global recovery story, you better take Kyle Bass's advice and load up on energy and commodities early in 2016. In fact, in terms of stocks, some portfolio managers think now is the time to load up on over-leveraged energy companies like Canada's Baytex Energy (BTE) which got decimated in 2015 (there were plenty of others that got killed last year).

Given my macro outlook, I believe there are a lot of risks investing or trading in energy and commodity stocks and this could once again turn out to be the biggest sucker trade of the year.

Sure, experienced traders will make money playing the swings in these beaten down names but most traders and investors should continue steering clear of energy (XLE), Metals and Mining (XME), Oil & Gas Exploration (XOP) and commodities (GSG) in general because downside risks remain too high.

As far as oil, I agree with BP's CEO Bob Dudley, the slump in global oil prices could hit bottom in early 2016 but prices are likely to remain low for the next couple of years. I personally see oil prices heading to the mid to low 20s in the first half of the year and they will stay low for a very long time, especially if global deflation sets in (keep shorting oil futures and the CAD on any pop!).

If you are dead set on investing in this space, go for quality names with great balance sheets and avoid over-leveraged names which will go bankrupt in a deflationary world.

Emerging Markets

Emerging markets look like another classic boom bust story and we're now living through the bust cycle. Deflation is wreaking havoc in China and Japan and I would continue steering clear of Chinese (FXI) and emerging markets shares (EEM) altogether in 2016.

Healthcare and Biotech

In late August 2015, I recommended loading up on biotechs and still like this sector a lot. But as the risks of global deflation rise, RISK OFF markets will dominate in 2016 and it will mean a lot more volatility for high flying, high beta and speculative biotech stocks. Still, there are great opportunities in this sector and even though some analysts are focusing only on big names, it's some of the smaller names that I think have great potential going forward.

What is clear to me however is that demographic shifts around the world augur well for Healthcare (XLV), big (IBB) and small (XBI) biotech stocks but it will be volatile and there will be many winners & losers in this space. This is why I track the top biotech and healthcare funds to see where they are focusing their attention.

Retail

It's not just energy and commodity names that got hit in 2015. A lot of retail stocks (XRT) like Macy's (M), Michael Kors (KORS) and Wal-Mart (WMT) also got clobbered in 2015 and this despite the huge drop in oil and gas prices. This is particularly worrisome because it means Americans are spending less, saving more and paying off their huge debts (all of which reinforces deflation coming to America). Stocks like Amazon (AMZN) soared in 2015 because in a deflationary world, price and convenience matter more than ever (still, be careful with this high flyer, as a pairs trade, I would short Amazon and go long Wal-Mart in 2016!!).

Bonds, Utilities and High Dividend Stocks, and Financials

These are all related. Billionaire Paul Singer expanded his "bigger short" thesis and lots of people are very nervous on bonds, especially high yield bonds (HYG) which are reeling as oil prices keep dropping. Still, even though I see continued weakness in high yield, I don't think the high yield blow-up will crash markets.

And even though the Fed is quite stupidly raising rates in the absence of inflation, this will only make its deflation problem worse down the road, which is very bond friendly.

Importantly, keep your eye on the 5-year, 5-year forward inflation expectation rate courtesy of the St-Louis Fed (click on image):

This chart isn't exactly screaming for higher rates and I'm worried that if the Fed goes ahead and raises rates gradually in a world full of deflation, inflation expectations will keep going lower.

This is why I find it hard to short U.S. government bonds (TLT) in this environment and think a lot of bond bears have it all wrong, just like those JGB bears which got killed shorting Japanese bonds throughout the last 20 years (click on image):

Given the risks of deflation, high dividend stocks (VYM) and Utilities (XLU) should continue to do well but this trade is crowded and there will be pullbacks on any sign of global growth as yields pick up (it's all part of a RISK OFF/ defensive trade which moves as algos switch the lights on and off).

Conversely, I'm less bullish on Financials (XLF) in a deflationary world and think big banks and big insurance companies have all sorts of structural headwinds to deal with in the years ahead. One issue for big banks is how are they going to deal with less revenues from their big hedge fund and private equity clients which are struggling to deliver absolute returns. There will be more M&A activity to offset this loss but I think Financials are going to have a very tough slug ahead.

Still, one former bond trader at the Caisse told me he sees value in preferred shares of Canadian banks as they got whacked hard in 2015 and he might be right on that call. But I'm increasingly worried that a long Canadian economic crisis is slowly unfolding and I see negative rates in Canada in the near future, which doesn't augur well for financial stocks.

In a nutshell, those are my market thoughts. At this writing, there's no "January Effect" taking place in the stock market as worries from China keep clobbering risk assets. In this environment, investors should expect less and buy antacid to deal with huge fluctuations in stocks (don't worry, there will be big rallies and big dips ahead!!).

Lastly, Mr. Black Swan, Nassim Taleb, wrote an interesting comment for the Wall Street Journal on the real financial risks of 2016 where he stated he isn't worried about banks as they shed a lot of risk-taking activity but he is worried about commodity producers:

Second, Harry S. Dent, author of The Demographic Cliff and editor of the free newsletter Economy & Markets. Harry is way too bearish for me but he highlights important demographic trends that will determine long-term trends in markets. He also discusses why global deflation, not inflation, is the main threat policymakers will be grappling with for a very long time.

Also, the Federal Reserve will regret its interest rate hike in December and will be forced to backtrack in 2016, closely followed market watcher Jim Grant said Monday, as global stock markets were selling off on Chinese economic weakness. I agree, the Fed will have to backtrack in 2016 or risk global deflation.

And finally, please remember to kindly donate and/ or subscribe to this blog on the top right-hand side under my ugly mug. Thank you and have a Happy and Healthy New Year!

As the year 2015 comes to termination, there seems to be no equivalent end to the deflationary current blight. Global deflation traces its origin to the depth of the "great financial recession" (2008-2010).Unlike Bechloss, I trace the origins of global deflation back to the tech bubble and crash of 2000-2002. It's only manifesting itself right now because China's super-boom has ended abruptly, wreaking havoc on commodities and heightening the risks of deflation.

Those of us who lived through the surge of what seemed to be a never-ending inflationary spiral transcending two decades (1965-85) could hardly imagine that a diametric opposite would manifest itself so dramatically in a relatively short time period. This has witnessed an overwhelming reversal of economic factors. A reasonable explanation might emerge from the particular circumstances that predominated during the respective inflationary and the current "deflationary" periods:

As the post World War II period witnessed an unexpected rise in population and its accompanying economic demand, critical shortages in all aspects of emerging economic needs became obvious, especially in the U.S., Japan and Central and Western Europe. Together with the upwardly mobile hundreds of millions seeking and gaining higher living standard, shortages in all aspects of improved civilized living emerged simultaneously. This manifested itself in higher wages for all types of working groups, more often than not unionized; and unprecedented consumer demand embracing residential and commercial construction, automobiles, and the many other indicators of an upwardly evolving consumer sector. In the U.S., it had reached a world record of 70% of its gigantic gross domestic product.

In effect, it had created an unprecedented demand surge, never before experienced so voluminously throughout most of the Western world. This resulted in supply shortages all at once, which were further exacerbated; first by Japan, then the unprecedented Chinese economic miracle that brought this supply/demand inversion to new heights.

While such surging demand was eventually matched by voluminous supply, which seemed to create an overall economic balance by the time of the millennial 2000 year transition, China, India, and other emerging Southeast Asian nations upped the demand push upward even further, especially in such critical commodities as oil, copper, iron ore (steel), etc., and agricultural products.

That accelerating demand/supply imbalance came to an abrupt end with the sudden reversal created by the now well-publicized "great financial recession." This not only generated a sudden oversupply of production capability, employees, and tangible goods, but put the world's financial leadership into a state of disarray.

This has recently been further aggravated by the sudden removal of China from becoming the buyer of last resort of just about all the goods the world has had to offer through its expanded capability. At the same time, an evolving technology is making an oversupply of hands-on workers less necessary than ever before; and this is coming at a time when labor force participation in the industrialized world has hit a new statistical low. While the demand/supply aspects of "inflation" will have run its course, the employment reversal will be much harder to rectify.

Importantly, I don't see any end to the deflation supercycle and have outlined six structural themes which support my long-term outlook on global deflation:

- The global jobs crisis: Jobs are vanishing all around the world at an alarming rate. Worse still, full-time jobs with good wages and benefits are being replaced with part-time jobs with low wages and no benefits.

- Demographics: The aging of the population isn't pro-growth. As people get older, they live on a fixed income, consume less, and are generally more careful with their meager savings. The fact that the unemployment rate is soaring for younger workers just adds more fuel to the fire. Without a decent job, young people cannot afford to get married, buy a house and have children.

- The global pension crisis: A common theme of this blog is how pension poverty is wreaking havoc on our economy. It's not just the demographic shift, as people retire with little or no savings, they consume less, governments collect less sales taxes and they pay out more in social welfare costs. This is why I'm such a stickler for enhanced CPP and Social Security, a universal pension which covers everyone (provided governments get the governance and risk-sharing right).

- Rising inequality: Rising inequality is threatening the global recovery. As Warren Buffett once noted, the marginal utility of an extra billion to the ultra wealthy isn't as useful as it can be to millions of others struggling under crushing poverty. But while Buffett and Gates talk up "The Giving Pledge", the truth is philanthropy won't make a dent in the trend of rising inequality which is extremely deflationary because it concentrates wealth in the hands of a few and does nothing to stimulate widespread consumption.

- High and unsustainable debt in the developed world: Government and household debt levels are high and unsustainable in many developed nations. This too constrains government and personal spending and is very deflationary.

- Technology: Everyone loves shopping on-line to hunt for bargains. Technology is great in terms of keeping productivity high and prices low, but viewed over a very long period, great shifts in technology are disinflationary and some say deflationary (think Amazon, Uber, etc.).

And all this financial risk-taking can end very badly in a deflationary environment. In fact, Graham Summers, Chief Market Strategist for Phoenix Capital Research published a comment, Deflation is Back… Will It Lead to Another Market Crash?:

Central Bankers are flummoxed. Having cut interest rates over 600 times since 2009 (and printed over $15 trillion), they’ve yet to generate the expected economic growth.

Despite these failures, the ECB, and the Bank of Japan are currently engaging massive QE programs. The Fed is the only major Central Bank not rapidly expanding its balance sheet.

Why, after six years, are we still seeing such aggressive policies?

Because deflation, the bad kind, is once again lurking around the corner.

Anyone with a functioning brain knows that deflation is a good thing. No one complains when they are able to buy something at a lower price, whether it is a home, gasoline, or computer.

However, debt deflation is a different story. Debt deflation means that future debt payments are becoming more expensive. This means that debt servicing will become more difficult, eventually leading to default and debt restructuring.

It is debt deflation that remains the primary focus for the global Central Banks. Indeed, if you consider the threat of debt deflation, every Central Bank move makes sense. ZIRP, NIRP, and QE all have the same goal in mind: to lower interest rates and push bonds higher (thereby making sovereign debt loads more serviceable).

With this in mind, even a whiff of debt deflation is enough to give Central Bankers nightmares. It’s also why they are so fond of inflation via currency devaluation, as it permits them to render massive debt loads more serviceable.

Unfortunately, the great “reflation experiment” is failing. Indeed, as Societe General has noted, it appears the developed world may be “turning Japanese” i.e. moving into a long-term deflationary cycle similar to that which has plagued Japan for the last 20 years.

To whit, inflation expectations are collapsing globally.

In Europe, despite three cuts into NIRP, the announcement of QE and an extension of QE, inflation is barely positive at 0.2%.

Then of course there is the US.

There, one of the better measures of inflation expectations is the 5 Year, 5-Year Forward Inflation Expectation Rate. That is simply a long way of saying that this chart measures where investors expect inflation to be in five years… and running for five years after that date.

As you can see, inflation expectations have collapsed in the latter half of 2015. Post-2008, any time this measure has fallen below the Fed’s desired threshold of 2%, it has launched a new monetary policy. In 2010 it was QE 2. In 2011 it was Operation Twist.

We’re now well below that level. And this is AFTER six years of ZIRP and $4 trillion in QE!

Deflation is back… and as it rears its head again in the west, Western Central Banks will soon be forced to answer the question: Can we actually stop deflation?

Unfortunately for them, the answer is likely no.

Consider Japan.

Japan has engaged in NINE QE programs since 1990. Since that time, the country’s GDP growth has been anemic at best. Indeed, even its latest MASSIVE QE program (a single monetary program equal to 25% of Japan’s GDP) only boosted Japan’s GDP for two quarters before growth rolled over again. Indeed, Japan is once again back in technical recession as of our writing this.

The reality is slowly beginning to sink in that Central Banks cannot put off the business cycle. They’ve spent over $15 trillion and cut interest rates over 600 times and all they’ve generated is one of the weakest recoveries on record.Graham Summers posted a follow-up blog comment on why he thinks 2016 will bring another 2008-type crash (part 1) basically stating that Japan and Europe are screwed and concluding:

What happens the next time global GDP takes a nosedive when Central Banks have already used up all of their ammunition?

"Between these two banking systems alone, you’ve got the makings of a global financial crisis at least on par with 2008. Both countries are sinking into deflation at a time when their respective Central Banks have little if any ammo left."This is where I start tuning out from Summers who unsurprisingly has published his bearish material extensively on Zero Hedge and fits perfectly with that blog's doom and gloom outlook on markets.

It's not that I disagree with his main thesis -- namely, the world has a major deflation problem which is causing policymakers all sorts of angst and can lead to a huge market crash -- but when I read stuff like "central banks are running out of ammo," I just tune off.

Why? Because as I've repeatedly explained, despite Ray Dalio being worried about the next downturn, central banks have plenty of options beyond zero rates and more QE as they try to save the world from a prolonged period of debt deflation and one of those options is negative interest rates which have been used in Switzerland and elsewhere in Europe and are coming to Canada in the near future.

All this to say, despite what Ray Dalio and Bill Gross think, the Martingale casinos aren't about to go bust any time soon and central banks are a lot more clever than hedge fund and market gurus give them credit for.

Having said this, central banks are not going to solve all the world's economic and financial ills and there are serious challenges ahead which will only get worse once global deflation sets in.

On this last point, Carmen Reinhart, Professor of the International Financial System at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government wrote a great comment for Project Syndicate, A Year of Sovereign Defaults?:

When it comes to sovereign debt, the term “default” is often misunderstood. It almost never entails the complete and permanent repudiation of the entire stock of debt; indeed, even some Czarist-era Russian bonds were eventually (if only partly) repaid after the 1917 revolution. Rather, non-payment – a “default,” according to credit-rating agencies, when it involves private creditors – typically spurs a conversation about debt restructuring, which can involve maturity extensions, coupon-payment cuts, grace periods, or face-value reductions (so-called “haircuts”).Reinhart is right, the risks of another emerging markets crisis are rising fast, and the lingering effects of China's Big Bang and the Fed's myopic and silly focus on 'normalizing rates' in the absence of inflation could prove to be the final death knell for emerging markets.

If history is a guide, such conversations may be happening a lot in 2016.

Like so many other features of the global economy, debt accumulation and default tends to occur in cycles. Since 1800, the global economy has endured several such cycles, with the share of independent countries undergoing restructuring during any given year oscillating between zero and 50% (see figure below). Whereas one- and two-decade lulls in defaults are not uncommon, each quiet spell has invariably been followed by a new wave of defaults.

The most recent default cycle includes the emerging-market debt crises of the 1980s and 1990s. Most countries resolved their external-debt problems by the mid-1990s, but a substantial share of countries in the lowest-income group remain in chronic arrears with their official creditors.

Like outright default or the restructuring of debts to official creditors, such arrears are often swept under the rug, possibly because they tend to involve low-income debtors and relatively small dollar amounts. But that does not negate their eventual capacity to help spur a new round of crises, when sovereigns who never quite got a handle on their debts are, say, met with unfavorable global conditions.

And, indeed, global economic conditions – such as commodity-price fluctuations and changes in interest rates by major economic powers such as the United States or China – play a major role in precipitating sovereign-debt crises. As my recent work with Vincent Reinhart and Christoph Trebesch reveals, peaks and troughs in the international capital-flow cycle are especially dangerous, with defaults proliferating at the end of a capital-inflow bonanza.

As 2016 begins, there are clear signs of serious debt/default squalls on the horizon. We can already see the first white-capped waves.

For some sovereigns, the main problem stems from internal debt dynamics. Ukraine’s situation is certainly precarious, though, given its unique drivers, it is probably best not to draw broader conclusions from its trajectory.

Greece’s situation, by contrast, is all too familiar. The government continued to accumulate debt until the burden was no longer sustainable. When the evidence of these excesses became overwhelming, new credit stopped flowing, making it impossible to service existing debts. Last July, in highly charged negotiations with its official creditors – the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund – Greece defaulted on its obligations to the IMF. That makes Greece the first – and, so far, the only – advanced economy ever to do so.

But, as is so often the case, what happened was not a complete default so much as a step toward a new deal. Greece’s European partners eventually agreed to provide additional financial support, in exchange for a pledge from Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s government to implement difficult structural reforms and deep budget cuts. Unfortunately, it seems that these measures did not so much resolve the Greek debt crisis as delay it.

Another economy in serious danger is the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, which urgently needs needs a comprehensive restructuring of its $73 billion in sovereign debt. Recent agreements to restructure some debt are just the beginning; in fact, they are not even adequate to rule out an outright default.

It should be noted, however, that while such a “credit event” would obviously be a big problem, creditors may be overstating its potential external impacts. They like to warn that although Puerto Rico is a commonwealth, not a state, its failure to service its debts would set a bad precedent for US states and municipalities.

But that precedent was set a long time ago. In the 1840s, nine US states stopped servicing their debts. Some eventually settled at full value; others did so at a discount; and several more repudiated a portion of their debt altogether. In the 1870s, another round of defaults engulfed 11 states. West Virginia’s bout of default and restructuring lasted until 1919.

Some of the biggest risks lie in the emerging economies, which are suffering primarily from a sea change in the global economic environment. During China’s infrastructure boom, it was importing huge volumes of commodities, pushing up their prices and, in turn, growth in the world’s commodity exporters, including large emerging economies like Brazil. Add to that increased lending from China and huge capital inflows propelled by low US interest rates, and the emerging economies were thriving. The global economic crisis of 2008-2009 disrupted, but did not derail, this rapid growth, and emerging economies enjoyed an unusually crisis-free decade until early 2013.

But the US Federal Reserve’s move to increase interest rates, together with slowing growth (and, in turn, investment) in China and collapsing oil and commodity prices, has brought the capital inflow bonanza to a halt. Lately, many emerging-market currencies have slid sharply, increasing the cost of servicing external dollar debts. Export and public-sector revenues have declined, giving way to widening current-account and fiscal deficits. Growth and investment have slowed almost across the board.

From a historical perspective, the emerging economies seem to be headed toward a major crisis. Of course, they may prove more resilient than their predecessors. But we shouldn’t count on it.

In fact, The Economist notes Brazil’s economy may be 8% smaller than it was in the first quarter of 2014, when it last saw growth; GDP per person could be down by a fifth since its peak in 2010, which is not as bad as the situation in Greece, but not far off. Moreover, Brazil's debt is expected to reach 93% of GDP in 2019, a situation which can quickly become untenable if the global economy sinks into deflation.

Also, Bloomberg reports South Korea’s biggest brokerage predicts the won is headed for its steepest annual slide in eight years as the government favors depreciation to revive exports and stave off deflation.

South Korea's economic woes will only get worse if China's slowdown persists as it grapples with deflation. JP Smith, who worked at Deutsche Bank before leaving last year to start independent research firm Ecstrat, says conditions in China look as ominous as those in the U.S. on the eve of the 2008 financial crisis, and in Korea just before the 1997 Asian crisis. As a result, Chinese stocks face greater downside potential than those of any other global market, he wrote in a Dec. 17 report.

And if China decides to once again devalue its currency, it will have ripple effects throughout Asia, including Japan where the prime minister and central bank governor have applied fresh pressure on companies to do their part in putting a sustained end to deflation by boosting wages and investment, with little success.

All this to say keep monitoring emerging market currencies in 2016. This is where you will see the global battle against deflation take place. Unfortunately, it's a losing battle and one that will export disinflation and deflation throughout the world at the worst possible time.

In my opinion, the problems in emerging markets are only going to get worse in 2016 so I have a hard time buying the global recovery theme which some elite funds are betting on. Even Canada's large and powerful pensions are betting on energy but those investments might not pan out for years or worse still, decades if global deflation sets in.

Above, I've given you my broad global macro thoughts for the year. I see deflationary headwinds picking up all over the world, especially emerging markets where the risks of another financial crisis are rising. I see no global recovery taking place and think those betting on one are going to once again be sorely disappointed.

Interestingly, in his 2016 Economic Outlook: Consensus and Other Views, Ted Carmichael does a masterful job demonstrating just how (overly) optimistic consensus forecasts are for 2016. I highly recommend you to read his entire comment here where he's very careful and much more balanced than most economists out there and concludes by noting the following:

2015 turned out to be a third consecutive year in which global growth was modestly disappointing, but the real story for markets was the divergences in real GDP growth. Will the divergences of 2014-15 continue? If so, the US Fed will likely be joined by the Bank of England and perhaps a few other central banks in tightening monetary policy in 2016, while the ECB, BoJ and PBoC will likely maintain their current accommodative policies or ease further. In this scenario, the US$ is likely to continue to appreciate against currencies of countries whose central banks remain accommodative. Further appreciation of the US dollar combined with below trend growth in China, Brazil and Russia will, barring a major geopolitical event, will likely continue to weigh on commodity prices and the currencies of commodity exporting countries.I'm in agreement with Ted on all these questions and think too many economists and strategists are way too optimistic on the global recovery, completely underestimating the potential of an emerging markets crisis and the ravaging effects this will have on markets and global deflation. This is especially problematic if the Fed continues to raise rates in the absence of any inflation pressure.

The questions one should ask about 2016 consensus forecasts are the same as we asked a year ago:

A year ago, my answers to these questions were: No, No, Don't Know, Unlikely, and Probably. I can see little reason to change these answers as we head into 2016. In the near future, I will turn to the question of how Canadian investors should think about 2016 as another year with macro risks skewed to the downside.

- Can the macro divergences between above-trend growth in some key DM economies and below-trend growth in key EM economies be sustained without serious financial instability in some countries and significant volatility in global currency and financial markets?

- Can commodity prices stabilize and recover even as the USD continues to rally and global commodity supply continues to outpace global demand.

- Can China and other EM economies prevent hard landings for their over-leveraged economies?

- Can Canada and Australia, with overheated housing markets, rebound to grow at or above trend after a sharp fall in commodity prices and as the Fed continues to raise its policy rate?

- Will we look back on 2016 as yet another year that started with optimistic forecasts and ended with disappointment?

Bearing the above global macro outlook in mind, I will now shift my attention to markets.

First, Julie Verhage of Bloomberg did a great job going over the best and worst-performing assets of 2015, a year where nothing worked for global asset allocators. You should take the time to look at the charts she posted in her comment.

What else? Sam Ro and Andy Kiersz of Business Insider went over the S&P 500's 10 biggest winners and 10 biggest losers of 2015:

Stocks didn't go nowhere in 2015. Many stocks most certainly went somewhere.Not surprisingly, you will see any currency, stock or bond related to energy, commodities and metals got clobbered in 2015, which leads me straight to the trillion dollar question: Will 2016 be the year of mean reversion, especially if global growth surprises to the upside?

Here's a snapshot of the S&P 500's biggest winners and losers in 2015.

First the winners: Leading the way are Netflix and Amazon, two of the so-call "FANG" stocks. Generally, tech and consumer discretionary stocks were among the biggest winners this year, capitalizing on themes like disruption and consumer spending.

Dominating the losers are the commodities and basic materials companies. There's little surprise here as depressed prices for things like oil and copper crushed profit margins.

If you believe in the global recovery story, you better take Kyle Bass's advice and load up on energy and commodities early in 2016. In fact, in terms of stocks, some portfolio managers think now is the time to load up on over-leveraged energy companies like Canada's Baytex Energy (BTE) which got decimated in 2015 (there were plenty of others that got killed last year).

Given my macro outlook, I believe there are a lot of risks investing or trading in energy and commodity stocks and this could once again turn out to be the biggest sucker trade of the year.

Sure, experienced traders will make money playing the swings in these beaten down names but most traders and investors should continue steering clear of energy (XLE), Metals and Mining (XME), Oil & Gas Exploration (XOP) and commodities (GSG) in general because downside risks remain too high.

As far as oil, I agree with BP's CEO Bob Dudley, the slump in global oil prices could hit bottom in early 2016 but prices are likely to remain low for the next couple of years. I personally see oil prices heading to the mid to low 20s in the first half of the year and they will stay low for a very long time, especially if global deflation sets in (keep shorting oil futures and the CAD on any pop!).

If you are dead set on investing in this space, go for quality names with great balance sheets and avoid over-leveraged names which will go bankrupt in a deflationary world.

Emerging Markets

Emerging markets look like another classic boom bust story and we're now living through the bust cycle. Deflation is wreaking havoc in China and Japan and I would continue steering clear of Chinese (FXI) and emerging markets shares (EEM) altogether in 2016.

Healthcare and Biotech

In late August 2015, I recommended loading up on biotechs and still like this sector a lot. But as the risks of global deflation rise, RISK OFF markets will dominate in 2016 and it will mean a lot more volatility for high flying, high beta and speculative biotech stocks. Still, there are great opportunities in this sector and even though some analysts are focusing only on big names, it's some of the smaller names that I think have great potential going forward.

What is clear to me however is that demographic shifts around the world augur well for Healthcare (XLV), big (IBB) and small (XBI) biotech stocks but it will be volatile and there will be many winners & losers in this space. This is why I track the top biotech and healthcare funds to see where they are focusing their attention.

Retail

It's not just energy and commodity names that got hit in 2015. A lot of retail stocks (XRT) like Macy's (M), Michael Kors (KORS) and Wal-Mart (WMT) also got clobbered in 2015 and this despite the huge drop in oil and gas prices. This is particularly worrisome because it means Americans are spending less, saving more and paying off their huge debts (all of which reinforces deflation coming to America). Stocks like Amazon (AMZN) soared in 2015 because in a deflationary world, price and convenience matter more than ever (still, be careful with this high flyer, as a pairs trade, I would short Amazon and go long Wal-Mart in 2016!!).

Bonds, Utilities and High Dividend Stocks, and Financials

These are all related. Billionaire Paul Singer expanded his "bigger short" thesis and lots of people are very nervous on bonds, especially high yield bonds (HYG) which are reeling as oil prices keep dropping. Still, even though I see continued weakness in high yield, I don't think the high yield blow-up will crash markets.

And even though the Fed is quite stupidly raising rates in the absence of inflation, this will only make its deflation problem worse down the road, which is very bond friendly.

Importantly, keep your eye on the 5-year, 5-year forward inflation expectation rate courtesy of the St-Louis Fed (click on image):

This chart isn't exactly screaming for higher rates and I'm worried that if the Fed goes ahead and raises rates gradually in a world full of deflation, inflation expectations will keep going lower.

This is why I find it hard to short U.S. government bonds (TLT) in this environment and think a lot of bond bears have it all wrong, just like those JGB bears which got killed shorting Japanese bonds throughout the last 20 years (click on image):

Given the risks of deflation, high dividend stocks (VYM) and Utilities (XLU) should continue to do well but this trade is crowded and there will be pullbacks on any sign of global growth as yields pick up (it's all part of a RISK OFF/ defensive trade which moves as algos switch the lights on and off).

Conversely, I'm less bullish on Financials (XLF) in a deflationary world and think big banks and big insurance companies have all sorts of structural headwinds to deal with in the years ahead. One issue for big banks is how are they going to deal with less revenues from their big hedge fund and private equity clients which are struggling to deliver absolute returns. There will be more M&A activity to offset this loss but I think Financials are going to have a very tough slug ahead.

Still, one former bond trader at the Caisse told me he sees value in preferred shares of Canadian banks as they got whacked hard in 2015 and he might be right on that call. But I'm increasingly worried that a long Canadian economic crisis is slowly unfolding and I see negative rates in Canada in the near future, which doesn't augur well for financial stocks.

In a nutshell, those are my market thoughts. At this writing, there's no "January Effect" taking place in the stock market as worries from China keep clobbering risk assets. In this environment, investors should expect less and buy antacid to deal with huge fluctuations in stocks (don't worry, there will be big rallies and big dips ahead!!).

Lastly, Mr. Black Swan, Nassim Taleb, wrote an interesting comment for the Wall Street Journal on the real financial risks of 2016 where he stated he isn't worried about banks as they shed a lot of risk-taking activity but he is worried about commodity producers:

Though “another Lehman Brothers” isn’t likely to happen with banks, it is very likely to happen with commodity firms and countries that depend directly or indirectly on commodity prices. Dubai is more threatened by oil prices than Islamic State. Commodity people have been shouting, “We’ve hit bottom,” which leads me to believe that they still have inventory to liquidate. Long-term agricultural commodity prices might be threatened by improvement in the storage of solar energy, which could prompt some governments to cancel ethanol programs as a mandatory use of land for “clean” energy.On that note, I leave you with a couple of interesting interviews from the Power & Market Report with Albert K Lu to ponder what lies ahead. First, Louis James, a commodities expert and senior investment strategist at Casey Research discusses why there's more pain ahead for commodities.

Second, Harry S. Dent, author of The Demographic Cliff and editor of the free newsletter Economy & Markets. Harry is way too bearish for me but he highlights important demographic trends that will determine long-term trends in markets. He also discusses why global deflation, not inflation, is the main threat policymakers will be grappling with for a very long time.

Also, the Federal Reserve will regret its interest rate hike in December and will be forced to backtrack in 2016, closely followed market watcher Jim Grant said Monday, as global stock markets were selling off on Chinese economic weakness. I agree, the Fed will have to backtrack in 2016 or risk global deflation.

And finally, please remember to kindly donate and/ or subscribe to this blog on the top right-hand side under my ugly mug. Thank you and have a Happy and Healthy New Year!

Comments

Post a Comment